My friend recently approached me with a problem. He’s currently teaching a class on innovation to a group of eighth-grade students, and it’s not going well.

The topic of innovation sounds interesting to me, but his students don’t seem to share my enthusiasm. He tells me that many of his 8th-grade students are visibly disengaged and unmotivated to learn the topic.

My friend has tried traditional carrot and stick incentives with his students – promising good grades if they pay attention or warning they will fail the class and not move to the ninth grade with their friends if they don’t pay attention.

But these carrot and stick incentives only motivate his students for a few minutes before they go back to being disengaged and unmotivated to learn.

What should my friend do?

To find the answer I picked up the book “Drive.”

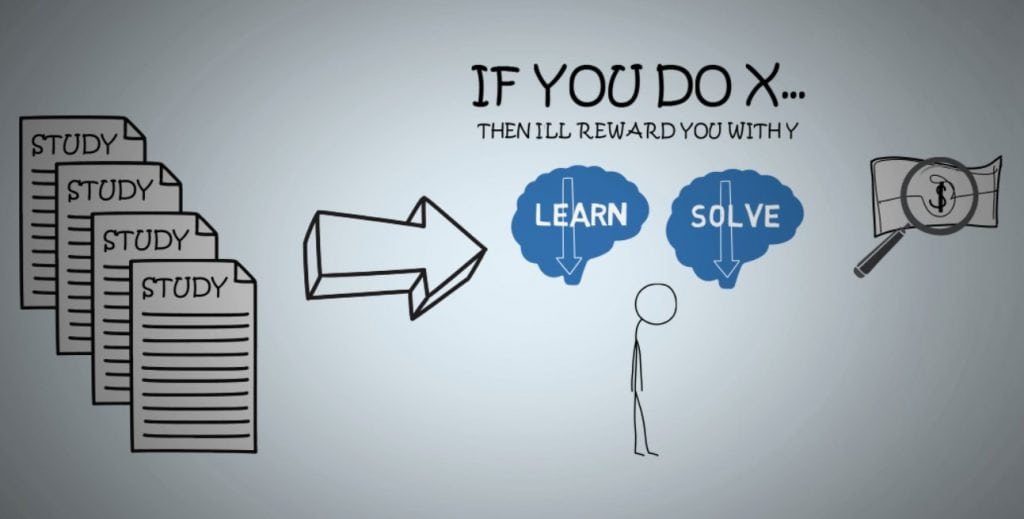

In the book, Author Daniel Pink details dozens of studies that reveal a shocking finding: if you try to motivate others with “if-then” incentives (i.e. if you do X, I’ll reward you with Y), you will strip any enjoyment out of the process of learning or working on hard problems.

In other words, if my friend continues to present carrot and stick incentives, he will do serious harm to his students’ natural willingness to learn and enjoy the process.

This counter-intuitive finding explains why many people who decide to turn their passion into a business (like becoming a surfing instructor) and focus primarily on money, kill their original passion and soon hate what they once loved doing for fun.

Rather than focusing on incentives that will kill his students’ natural willingness to learn, my friend should AMPlify his students’ intrinsic drive for learning. By AMPlifying his students’ intrinsic drive, his students will be more motivated to learn and more engaged during class.

Author Daniel Pink has uncovered three primary methods for AMPlifying intrinsic drivers. By understanding these three drivers, my friend might find a way to get his students engaged and motivated to learn.

PART 1:

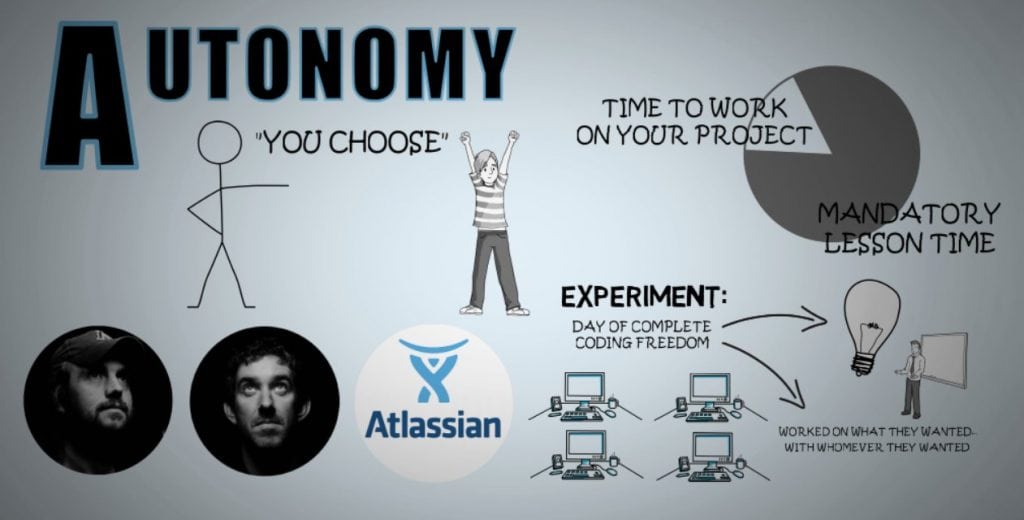

In 2002, Scott Farquhar and Mike Cannon-Brookes, two university graduates from Australia, wanted to make a decent salary and work for themselves.

With $10,000 in self-funding, they started a software enterprise company called Atlassian.

Over the years Mike and Scott grew the company, hired teams of programmers, and experienced moderate success. But they weren’t content. They wanted to improve their product and make Atlassian into a major player in the software enterprise market.

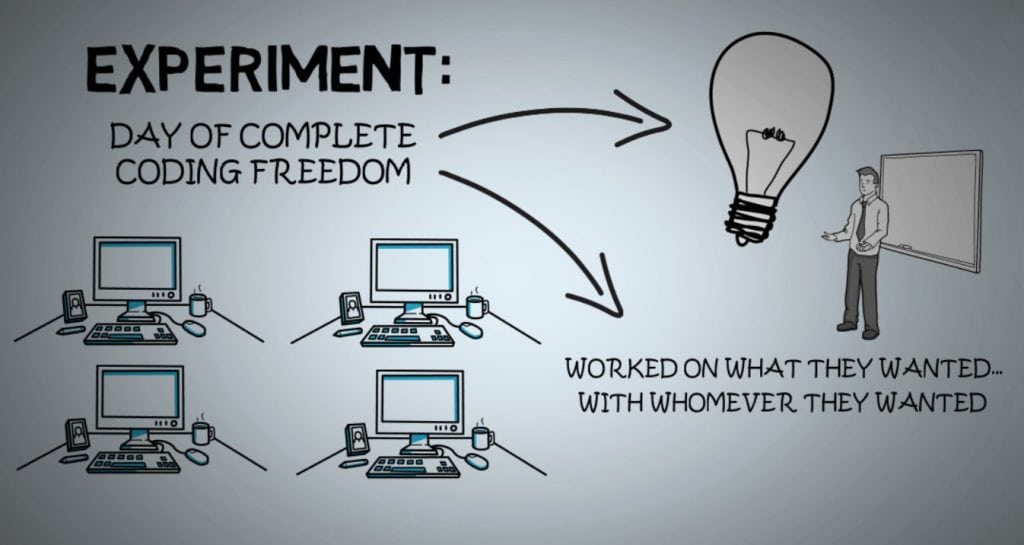

They tried an experiment that they hoped would spark innovation.

Mike and Scott gave each of their salaried programmers one day of complete freedom where they could work on whatever problem they wanted as long as they presented their results to the team the following day.

At two P.M. on Thursday, the Atlassian programmers started writing any code they wanted with whomever they wanted. Many of the programmers worked through the night.

At four P.M. on Friday, all the programmers gathered in a conference room with beer and chocolate cake on the table and presented the results to the group.

This crazy experiment led to crazy good results.

The programmers, fueled by a sense of freedom instead of cash incentives, came up with several new product ideas and dozens of creative solutions to existing problems.

If my friend wants his students to become motivated to learn his mandatory innovation class, he should take a page out of Atlassian’s book and spark a sense of autonomy.

My friend could set aside one class a week and allow his students to work on an innovation project of their choice.

He could give them tools, information, and supplies and let them choose a project that they want to work on with a team they want to work with.

The only condition would be they need to use the lessons taught in the class, and they need to present their learnings to the rest of the class at the end of the year.

Carving out a small amount of freedom and flexibility within a rigid framework can spark a surprising amount of drive and creativity.

PART 2:

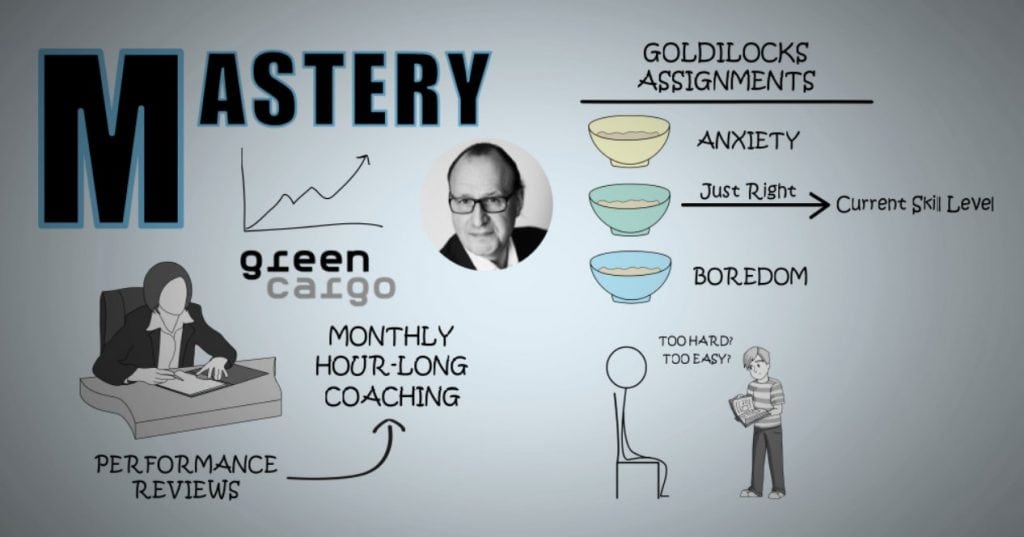

Most companies do a terrible job conducting performance reviews. But not Green Cargo. Green Cargo is a huge state-owned shipping company in Sweden.

In 2003, Stefan Falk joined the Green Cargo executive team and started overhauling Green Cargo’s performance review process.

Instead of having managers and employees meet once a year to discuss an employee’s performance, Green Cargo managers are required to meet with their employees once a month for an intense, hour-long, one-on-one coaching session.

During a performance review, a manager must get a sense whether their employee is overwhelmed or underwhelmed with their current work assignment and then find a way to craft Goldilocks work assignments for that employee.

A Goldilocks work assignment is an assignment that’s not too hard or too easy, but just above their current skill level. If an employee can find this Goldilocks work zone between boredom and anxiety, he or she is more likely to be engaged on the task at hand and feel a sense of mastery.

What effect did Green Cargo’s new performance review system have?

After a few months there was a noticeable increase in employee engagement, and after two years of these performance reviews, Green Cargo became profitable for the first time in 125 years.

If my friend wants to increase the engagement of his students, he should take a page out of Green Cargo’s playbook.

Each week he could make time to sit down with each of his students one-on-one and adjust the difficulty level on each of their assignments.

If a student finds an assignment too hard, my friend could adjust their next one by removing a question or two.

If a student finds an assignment too easy, the student could teach a struggling student the material to challenge their understanding and allow other students to catch up.

If he can get his students in a Goldilocks work zone on each of their assignments, he will spark the intrinsic drive for mastery and increase their overall engagement.

PART 3:

When Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg starts a meeting at Facebook, she always begins by stating the team’s mission.

In a recent interview, she said “You have to repeat your mission and your purpose…over and over and over. And sometimes you’re like, doesn’t everyone already know this? It doesn’t matter. Starting out the meetings with ‘This is Facebook’s mission…,’ ‘This is Instagram’s mission…,’ and ‘This is why Whatsapp exists…’ (is critical).”

When Sheryl Sandberg starts her meetings by stating the mission, she’s sparking the third intrinsic driver: a sense of purpose.

Purpose is the reason organizations like “Doctors Without Borders” can get highly skilled doctors to willingly travel to poor villages around the world, live in harsh conditions, and get paid very little money to do so. They do this because it fills them with a sense of purpose that comes from helping others.

If my friend wants to spark the intrinsic drive of purpose, he should introduce each topic by explaining how learning the topic will benefit people he cares about or a massive amount of people.

He could say: “Learning this innovation lesson will allow you to contribute more to your project team.”

Or

“This innovation principle is the same one Mark Zuckerberg used to build a product that billions of people love and use every day.”

If my friend wants his students to be more engaged and if we want our teams to be more motivated to solve hard problems, we need to stop offering incentives like bonuses or good grades or threating punishment for non-compliance.

We need to create a sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Summary by Nathan Lozeron