Imagine this evening you meet a friend for dinner. Halfway through dinner, you tell your friend you want to try an experiment. You’re going to spend 10 seconds tapping out a famous song on the table, and they have to guess what the song is.

You start to tap out the rhythm to the Happy Birthday song: Da, da-da-da, da-da…

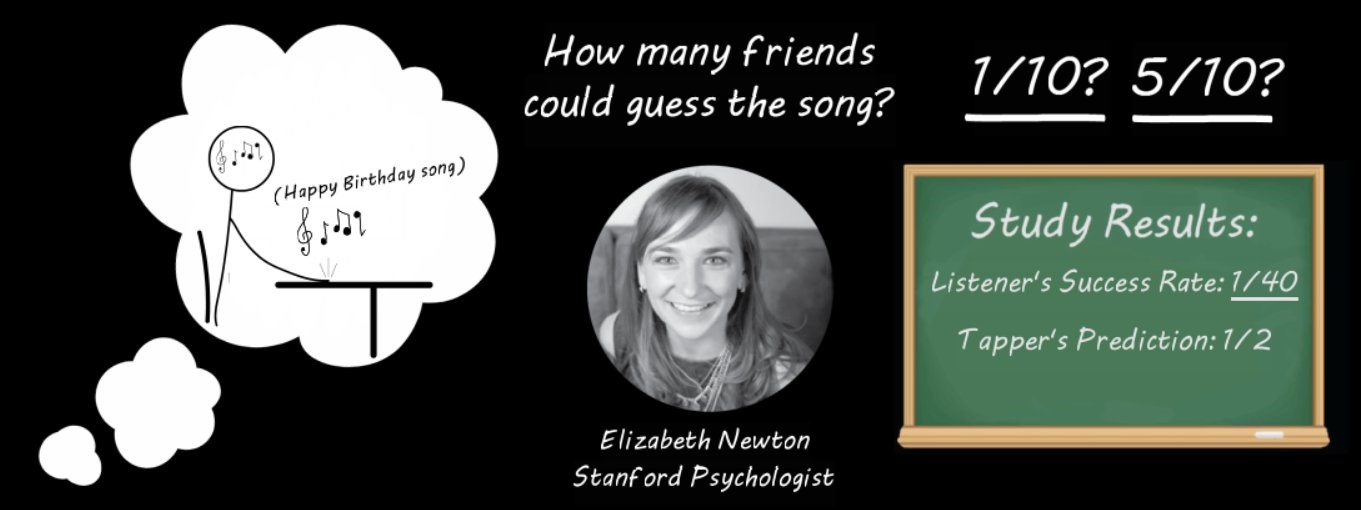

If you did that experiment with 10 friends, how many of those friends could guess the song? 1/10? 5/10?

In 1990 psychologist Elizabeth Newton played this game with students at Stanford University.

Her findings were startling:

Only 1 in 40 students could guess the famous song the tapper was tapping.

But here’s the troubling thing: the tappers thought at least half of the listeners could guess the song they were tapping.

Because the tappers knew the song and had the song playing in their head, they expected more people to know what song they were trying to communicate.

This is what psychologists call the curse of knowledge.

Most of the time we communicate our ideas as if we are the audience, and we forget that the audience doesn’t share our knowledge. This phenomenon makes our communication either confusing or boring.

The curse of knowledge is the reason brilliant scientists write papers few people can understand. Few people have that same level of expertise.

The curse of knowledge is the reason you can give a colleague straight-forward instructions, but those instructions seem confusing to that person.

The curse of knowledge is the reason you spend hours developing an interesting presentation, but everyone you present it to seems bored and distracted.

If you can’t communicate your ideas effectively, you waste time and effort developing your ideas.

Luckily authors Dan Heath and Chip Heath have found a way to counteract the curse of knowledge and get your ideas to stick.

Sticky ideas are interesting, actionable, and memorable.

The following three stories illustrate three methods for making your ideas stick.

PART 1:

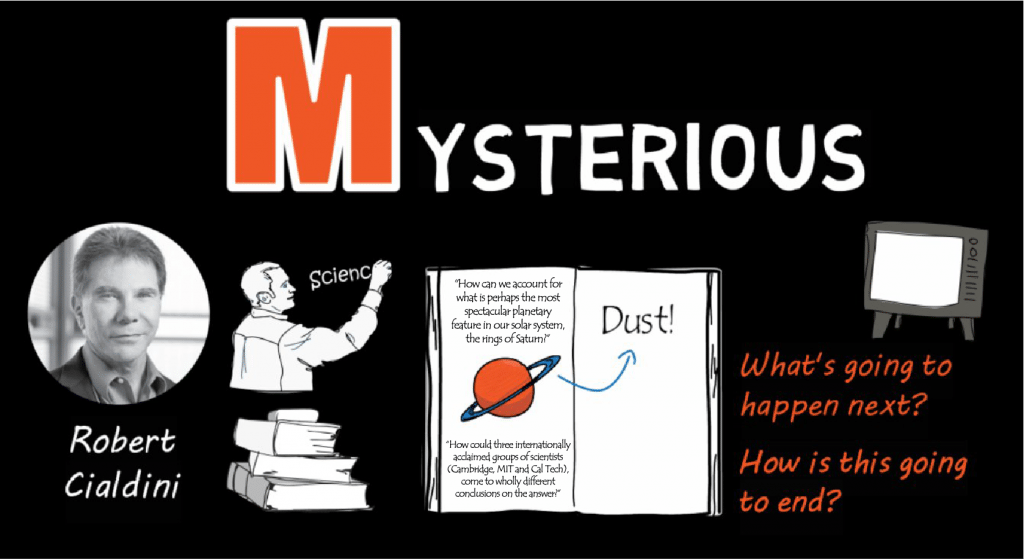

One afternoon, social psychologist Robert Cialdini went to the library to look for a compelling way to teach science lessons to his students at Arizona State University. He gathered a pile of scientific books to search for inspiration. As he flipped through the books, he found most were loaded with scientific jargon and painfully boring.

But then he came across an astronomy book that started with a question:

“How can we account for what is perhaps the most spectacular planetary feature in our solar system, the rings of Saturn? There’s nothing else like them. What are the rings of Saturn made of anyway?

“How could three internationally acclaimed groups of scientists (Cambridge, MIT and Cal Tech), come to wholly different conclusions on the answer?”

The answer unfolded slowly, like a great mystery novel. Cialdini had no interest in the rings of Saturn before picking up this book, but now he found himself going through the pages of this astronomy book like a speed reader.

The reason Cialdini couldn’t put that science book down is the same reason we force ourselves to sit through a bad movie: We need to know how it’s going to end.

If you want to make your ideas stick, don’t reveal your idea all at once. Create a sense of mystery.

I tried to do this at the beginning of this video by telling you I had three stories and then showed you three letters (M.U.P.). I hoped you would wonder what those letters stood for and what those stories were.

Authors Chip and Dan Heath say the goal is to get your audience thinking: “What’s going to happen next?” and “How is this going to end?” By getting your audience to ask those questions, you have a better chance at getting your audience engaged and making your ideas stick.

Oh, the answer to the Saturn mystery was Dust. That’s right Dust. Saturn’s rings are made of ice-covered dust.

PART 2:

The 2001 television commercial for the new enclave minivan opens with a minivan cruising down a suburban street. An off-camera voice states that the minivan has features like remote control sliding rear doors, a full Skyview sunroof, and a six-point navigation system. As the minivan cruises along the suburban streets, a family of five is smiling inside.

The minivan stops at an intersection, and the camera zooms into the face of the young boy in the back seat gazing out the window.

And then…WAAM!!

A speeding car barrels into the intersection and smashes into the minivan.

The minivan buckles and glass flies everywhere.

Then the screen fades to black and a message reads: “Didn’t see that coming? No one ever does. Buckle up.”

It wasn’t a car commercial. It was a safety commercial by the United States Department of Transportation.

That enclave minivan commercial caught the attention of millions of people when it aired in 2001 and effectively delivered a safety message most people found boring.

The enclave minivan commercial was effective because it was so unexpected. Nobody expects people to die in a car commercial.

Before delivering your next idea, capture the attention of your audience by injecting a dose of unexpectedness.

I tried to incorporate a dose of unexpectedness at the beginning of this video by suggesting the odds of guessing the tapped Happy Birthday song would be something like 1/10 or 5/10, and then I revealed the odds were more like 1/40. I was hoping that number would be surprising and insightful.

One great way to craft an unexpected message is to identify the topic of your idea and ask yourself: “What is my audience expecting to hear about this topic?”

Then ask yourself: “What would my audience find surprising or counterintuitive about this topic?”

When you ask these questions, you challenge the assumption that your audience will find your idea interesting solely because YOU find your idea interesting.

PART 3:

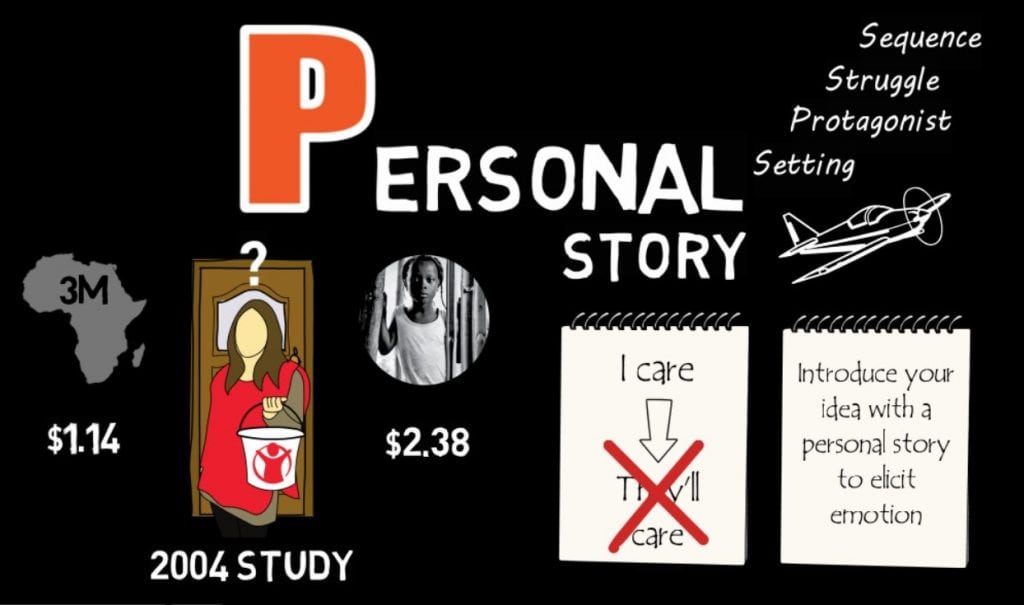

Take a moment and imagine someone knocking on your door. You open the door to find a young lady wearing a red vest and carrying a bucket. She politely introduces herself and explains that she’s working for ‘Save the Children’ and trying to raise money for starving children in Africa.

Which of her two calls for action are you more likely to donate to:

“Food shortages in Mali are affecting more than 3 million children. Please help them.”

OR

“Any money that you donate will go to Rokia, a seven-year-old girl from Mali, Africa. Rokia is desperately poor and faces the threat of severe hunger and starvation. Her life will be changed for the better as a result of your financial gift.”

In 2004, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University tested a similar scenario.

The people who were given the startling statistics about African food shortages contributed $1.14 on average.

But the people who read the personal story about Rokia contributed $2.38 on average. More than twice as much.

When you deliver a message to another person, you’re going to assume they’ll care about message because you care about the message (this is the curse of knowledge at work). But they won’t.

UNLESS you deliver your message with a personal story.

Stories are like flight simulators for the human mind. A personal story can allow someone to imagine themselves in the shoes of a character in a story and feel what they’re feeling.

This is the reason more people donated when they heard the Rokia story. Those donators felt Rokia’s pain and wanted to help.

If you want people to care about your ideas, introduce your ideas by using a personal story.

A good story involves a setting, a protagonist, a personal struggle, and a logical sequence of events to overcome that struggle. The goal is to make your idea the solution the character uses to overcome a struggle.

The protagonist in your story could be you, someone you know, or someone you read about.

TAKEAWAY:

To overcome the curse of knowledge, make your messages mysterious by asking questions, fill them with unexpected facts or events, and deliver them with a personal story.