Insights from the book ‘Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time‘ by Jeff Sutherland.

Time to Read: 8:26 minutes

Do you find most projects start off great but end up being a total nightmare to manage midway through?

Thanks to Jeff Sutherland’s book ‘Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time’ I no longer have project nightmares.

The Problem with Most Projects

The traditional method of executing a project goes something like this:

- one person is responsible for estimating and sequencing the activities needed to complete the project (makes assumptions for areas he/she is not an expert in)

- managers assign people to complete the activities

- the team sticks to the original plan until the project is complete (management assumes the original estimate will remain relevant throughout the entire project life-cycle)

- any change is seen as a threat to the project

- additional resources are spent trying to get the project back on track, according to the original (outdated) plan

This rigid approach to project management can often create products the customer doesn’t actually need in the end. It delivers a product that is more then they actually require and cost more money then they were willing to spend!

This traditional project management method is called the ‘Waterfall’ method. In the book ‘Scrum’, author Jeff Sutherland reflects on his experience with the ‘Waterfall’ method:

“The process was slow, unpredictable, and often never resulted in a product that people wanted or would pay to buy. Delays of months or even years were endemic to the process. The early step-by-step plans, laid out in comforting detail in Gantt charts, reassured management that they were in control of the development process – but almost without fail, we would fall quickly behind schedule and disastrously overbudget.” – Jeff Sutherland

The shortcomings of the ‘Waterfall’ method can be explained by the shortcomings of the human mind. Psychologists have found that we all use irrational mental shortcuts from time to time and are not aware that we are doing so. Psychologists call these shortcuts ‘cognitive fallacies’. Here are a two fallacies that the traditional ‘Waterfall’ method falls prey to:

1. Planning fallacy

The planning fallacy was first introduced by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. It states that we chronically underestimate the time it takes to complete something (even if we are aware of the phenomenon) because of our overconfidence in completing common tasks and our tendency to focus on a single isolated event without considering the influential factors.

A 1994 study called ‘Exploring the planning fallacy: Why people underestimate their task completion times’ asked 37 psychology students how long it would take them complete their thesis – identifying the best and worst-case scenarios. At the end of the study, researchers found that the actual completion dates occurred an average of 7 days later than the student’s worst-case estimates. Only 30% of students were able to stick to their original estimates.

We suffer from the planning fallacy whenever we estimate mid to large size projects.

“Estimates of work can range from 400 percent beyond the time actually taken to 25 percent of the time taken. The low and high estimates differ by a factor of sixteen. As the project progresses and more and more gets settled, the estimates fall more and more into line with reality until there are no more estimates, only reality.” – Jeff Sutherland

Therefore, a project plan is only useful if it can be refined in increments and updated according to the latest information we receive.

“The key is to refine the plan throughout the project rather than do it all up front. Plan in just enough detail to deliver the next increment of value, and estimate the remainder of the project in larger chunks. In Scrum, at the end of each iteration you have something of value that you can see, touch, and show to customers. You can ask them: “Is this what you want? Does this solve at least a piece of your problem? Are we going in the right direction?” And if the answer is no, change your plan.” – Jeff Sutherland

It is important to plan our projects. But we must ensure we do not ‘over plan’ our projects.

“A good plan executed violently now is better than a perfect plan executed next week” – General George S Patton Jr.

2. Sunken cost fallacy

If we use a large amount of time and resources to generate a project estimate we become overly attached to it. This attachment causes us to defend an original estimate, go over budget trying to maintain it and disregard new information that conflicts with it. When this occurs we are suffering from what psychologists call ‘the sunken cost fallacy’.

“The sunk-cost fallacy keeps people for too long in poor jobs, unhappy marriages, and unpromising research projects. I have often observed young scientists struggling to salvage a doomed project when they would be better advised to drop it and start a new one.” – Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Economist and author of ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’

If our initial estimate is too detailed we forget the true intent of the project and make the ‘plan’ the priority.

These two fallacies cause endless frustration when managing projects.

A New Way

In the 90’s, Japanese professors Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka did extensive research on some of the most effective companies in the world and found that they conducted projects in a radically different way then the Waterfall method.

Jeff Sutherland, author of ‘Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time’, used Takeuchi and Nonaka’s research to develop a project management system called ‘Scrum’ in the early 1990’s. Since then companies like Google, Amazon, Salesforce.com, Toyota and the FBI have used Scrum and continue to use it.

“Scrum has its origins in the world of software development. Now it’s sweeping through myriad other places where work gets done. Diverse businesses are using it for everything from building rocket ships to managing payroll to expanding human resources, and it’s also popping up in everything from finance to investment, from entertainment to journalism. Scrum accelerates human effort— it doesn’t matter what that effort is.” – Jeff Sutherland

Scrum can be used in almost every environment and on every type of project. I’ve used Scrum on my engineering projects and I now use it manage my website.

The 7 Steps of a Scrum Project

Identify the product owner (visionary), Scrum master (team facilitator) and a small team of 3 to 9 people that have all the skills necessary to complete a project phase.

(Scrum Sprint Checklist PDF – receive a condensed one-page checklist of the Scrum method)

- Create and Prioritize a Backlog (product owner responsibility)

- List everything that needs to be completed by the team, for the entire project, in narrative format: who, what, why (who’ll be getting value from it, what exactly do they need and why do they need it – “As an X, I want Y, so that I can do Z”).

- make each item small enough to estimate.

- make each item independent of other items (items can be considered “complete” on their own).

- ensure each item is ‘testable’ when completed (determine a testing method that you can use deem the item “complete”).

- Rank the items in terms of their customer value.

- Items that can provide immediate value and with relatively very little risk should be at the top of the list (prioritize items based on how quickly they can be demonstrated and used to generate revenue).

- List everything that needs to be completed by the team, for the entire project, in narrative format: who, what, why (who’ll be getting value from it, what exactly do they need and why do they need it – “As an X, I want Y, so that I can do Z”).

- Refine and Estimate Backlog Items (team’s responsibility)

- As a team, assign a Fibonacci number to each item: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 (a natural progression in nature that humans naturally find easier to make comparisons with).

- Start with one of the hardest/most complex items and assign it a value of 13 (use a higher Fibonacci number, like 21, 34 or 55 for very large projects). Make a relative comparison to this first item when assigning values to all other items.

- ”Do not estimate the Backlog in hours, because people are absolutely terrible at that” – Jeff Sutherland.

- Conduct a Sprint Planning Session (lead by the Scrum master)

- Establish a fixed sprint duration for the project that is no longer than 4 weeks (most people run a 1 or 2 week Sprints).

- Have the team determine how many points they think they can complete during the first Sprint (after the first Sprint they will have a benchmark value to use for future Sprints – aiming for a few more points each successive Sprint).

- Once the team has committed to what they think they can finish in one Sprint, that’s it. It cannot be changed or added to.

- Make Work Progress Visible (Scrum master’s responsibility)

- Create individual post-it notes for each sprint item and put them in one of three columns: DO, DOING, DONE.

- Move an item to ‘done’ directly after completing it.

- Update the Burndown Chart at the start of each day (a graph with ‘Sprint points’ on the y-axis and ‘Sprint days’ on the x-axis – starting with the total initial number of story points selected for the Sprint)

- The end result should be a steep downward slope that ends with zero points remaining on the last day of the Sprint.

- Conduct Daily Stand-up Scrum Meetings (lead by the Scrum master)

- Each day, at the same time, for no more than fifteen minutes, the team and the Scrum Master meet and answer three questions:

- What did we do yesterday to help the team finish the Sprint?

- What can we do today to help the team finish the Sprint?

- What obstacles could slow down our progress?

- Each day, at the same time, for no more than fifteen minutes, the team and the Scrum Master meet and answer three questions:

- Host a Sprint Demonstration (team’s responsibility)

- Invite all project stakeholders (customer, product owner, management, etc.).

- Show the results of what was completed during the last sprint.

- Only show items that meet the ‘Definition of Done’ (it does not need to be a complete product, but it should have at least one functional feature).

- Conduct a Sprint Retrospective Session (lead by the Scrum master)

- Gather feedback and comments from the demonstration session.

- Get the team together and have candid, solution-oriented discussion to answer the following questions:

- What went well?

- What could have been better?

- How can we improve the next Sprint?

Repeat steps 1-7 (briefly re-assessing steps 1 & 2 each sprint) until the customer is satisfied with the end result.

When you follow this method of work you don’t need to work as much.

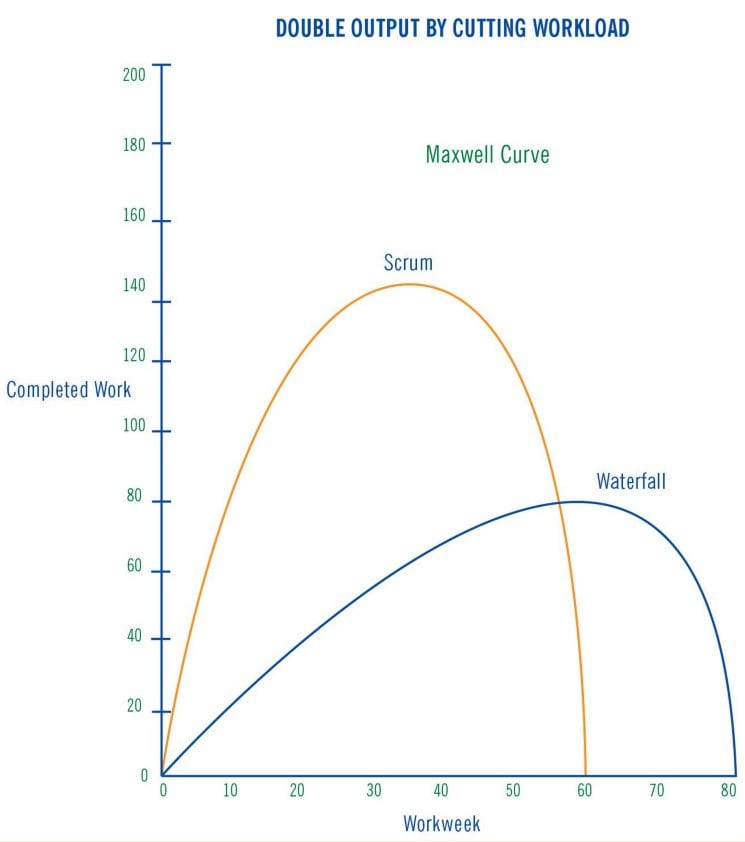

Maxwell Curve chart from the book ‘Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time’ by Jeff Sutherland (Chapter 5)

Why Scrum Works

Scrum works great because it embraces the following truths:

Compounding Improvement

Thanks to daily standup meetings and retrospective sessions scheduled no longer than 1 month a Scrum project continuously improves. Each improvement is build upon the previous improvement. When you improve a project process in this fashion you experience compounding improvement (aka: exponential improvement).

Most people are unable to grasp the power of compounding (me included!). We are all linear thinkers by nature. If I told you to take 30 linear steps 1 meter at a time, how far would you get? Easy, 30 meters.

But what if I told you to take 30 exponential one-meter steps: 1m step + 2m step + 4m step, etc. How far do you think you would be able to go?

Taking 30 exponential steps you take your 1,000,000,000 meters away from where you started. With 30 exponential steps you would circle the earth 78,000 times.

By having short sprints and frequent demonstrations we are able to harness the power of exponential improvement on our projects.

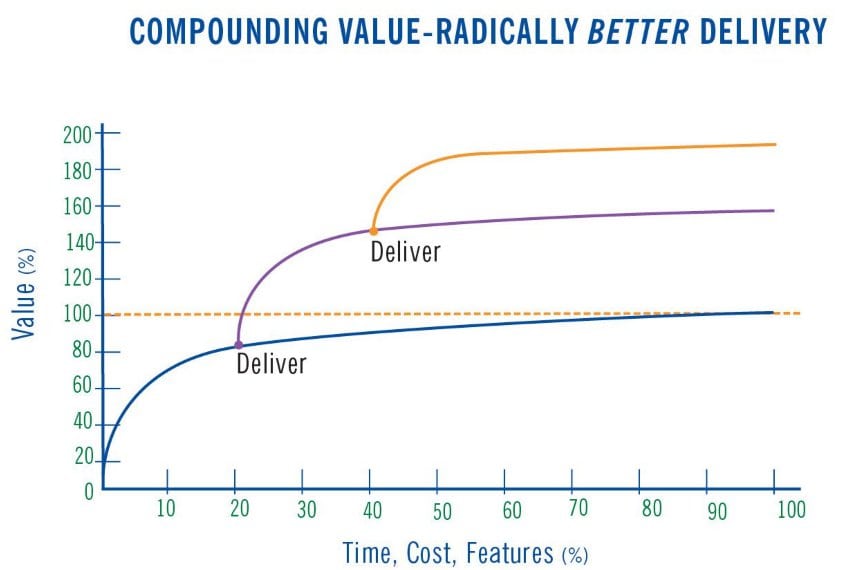

80/20 Production

In 1896, Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto found that most things follow an 80/20 distribution – 80% of the land was owned by 20% of the population, 80% of the wealth was in the hands of 20% of people, 80% of his peas grew from 20% of the pea pods. The Pareto Principle has become known as the ‘law of the vital few’: the majority of the output comes from a vital few inputs. Translated to our projects: the majority of value we deliver comes from a vital few tasks.

By finding and focusing on the 20% of available tasks on a given project for a given sprint we reduce the chances of working on something the customer may not need. The sprint duration should only allow enough time for 20% of the initial project activities to be completed before the next demonstration.

Compounding Value Chart from the book ‘Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time’ by Jeff Sutherland (Chapter 8)

When you deliver 80% value after each 20% time duration you end up delivering 350% of the expected project value (assuming you perform five 20% sprints during the project life-cycle – 80% value x 5 sprints = 350% overall value).

Reduced Decision Fatigue

If you don’t work in sprints (doing frequent demonstrations and retrospective sessions), you’re likely to waste a great deal of time doing things that are not essential to the project. This will require you to take extra time (overtime) to get the essential project components completed.

Working overtime leads to poor decision making. Poor decision making leads to mistakes, which leads to more work. It becomes a downward spiral towards burn out.

“People who work too many hours start making mistakes, which, as we’ve seen, can actually take more effort to fix then to create. Overworked employees get more distracted and begin distracting others. Soon they’re making bad decisions.” – CEO of Venture Capital firm OpenView states as detailed in the book ‘Scrum: Twice the work in the half the time’

Scrum validates results throughout the project lifecycle and ensures that very little time is wasted doing activities that produce minimal value. The system of Scrum forces you to be effective with your time and avoid overtime. When you reduce overtime you reduce decision fatigue and the rework that results from decision fatigue.

Intrinsic Motivation

In the book ‘DRIVE: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us‘, author Daniel Pink explains that people are driven by three powerful intrinsic motivations: purpose, mastery and autonomy. It turns out that intrinsic motivators last longer and are much more powerful than extrinsic motivators (i.e. more money).

Scrum taps into our three intrinsic motivators in the following way:

- Purpose: all team members establish and share a common goal to deliver the most value in the shortest amount of time.

- Mastery: continual improvement combined with visual progress generates a sense of mastery.

- Autonomy: team members focus on results instead of activities.

The TAKEAWAY

Use Scrum to make your projects vastly more enjoyable, rewarding and efficient than traditional project management methods.

What Now?

Turn your next project into a Scrum project by following the 7 steps of Scrum (click here for a handy one-page Scrum Sprint Checklist PDF).